Votes & Views #36

In my hands is this bible printed

in 1702. No, let me correct that –

the bible is much too big and heavy to hold – it is lying on a table in front

of me. A huge, stately book of

almost ten kilos, bound in wooden boards which have been covered with lovingly

anointed, but heavily cracked leather; the corners are protected by ornate brass

work, and two clasps keep it shut. I

open the book carefully; some newer pages have been inserted, covered with a

beautifully calligraphed genealogy, beginning in 1232 AD, of one of the old Cape families, the de Villiers clan.

I skim over some 4 pages of entries and come to the last name. He has asked me to find a new home for this

treasure, along with another couple of dozen stately, centuries-old books, and

many more recent books dealing with our subcontinent.

Most parents harbour a

hope that their children will one day have the same wish to preserve the

material things that they themselves cherished, used and collected to paper the

walls of their existence. That goes

for the family farm, the ancestral home, the antique furniture or jewellery –

and so often, books. However, since

times immemorial children have had their own headstrong ways. They stubbornly refuse to follow in their progenitors’

footsteps in matters of careers; spending habits; political views, consumption

of stimulants - and reading matter, among others.

A personal library is like a tree;

there is the seed – core books acquired on a specific subject or genre,

or

acquired as a ‘mystery’ lot at an auction; interest is stimulated and

broadens,

so more books are added. Tastes

branch out, mature and find other directions and so a collection grows.

After the proverbial three score years and ten or

thereabouts, comes the cut-off point in every collector’s life. Either

they decide to reduce their establishment

as it has become too cumbersome; they move into smaller, sheltered

accommodation, or their life reaches its conclusion.

In both cases material effects need to be redistributed and disposed of.

The natural inheritors are children and

grandchildren. No problem then. Or is there? The march of technology has

been

relentless; by now it has become a sprint with ever new entries into the

field. The rising generations have less dependence on the

printed word, there are more immediate, electronic, audiovisual forms of

media

on hand. Libraries take up large

amounts of space; they need care; they are subject to fire, damp and

insect

attack. That cherished

assemblage has suddenly become a

millstone round somebody’s neck.

Back in 1947, there

lived a family by the name of Solly near Sir Lowry’s Pass.

There are no Solly’s left in the Cape

that I can find, as the last of that name seem to have departed to live in

France, as the user of their telephone number informs me.

I picture a modestly well-off, aging

family, cultured people with varied interests, living in a large family home on

a farm overlooking False Bay. Their time came, there were no immediate heirs to

inherit. The executors of the estate

moved in and the house, furniture and effects were auctioned off and dispersed

- this much I know. Their small

library, containing some of the most prized works describing life and travels

during the 17th to 19th century in Southern

Africa, was bought by the de Villiers family, and became the

beginning of a new collection.

Now, some seventy years later,

that metamorphosed library has once more come to the end of its existence. The current owners, a few generations later, are

reducing their establishment, and are moving to a retirement village, where

there is no space for libraries. The

following generations have other interests and don’t want to ‘curate’ the books. New owners must be found, which is where I come

into the picture. After our initial contact and perusal of a

list of titles, almost two hundred volumes were dropped off at Africana Books. Since many of these were items I had not handled

before, I drove up to Cape Town ( as I live in the Tzitzikamma forest nowadays

) post-haste, and spent the next week working ten hours a day to acquaint

myself with just twenty of the most uncommon works.

Since these were written in mainly in Dutch and French – languages with which I

have some familiarity, but in which I am not entirely comfortable, this was a

slow process. Still, my findings

were a little like a Who’s Who of early travel round the Cape. So let me tell you about them in some sort of

chronological order.

The oldest item is a little

extract from Churchill’s Voyages, printed in 1707.

Written by Willem ten Rhyne in 1673, An Account of the Cape of Good Hope. The diary opens on 9 October 1673,

when Ten Rhyne’s ship anchored in Saldanha

Bay.

He writes an introduction on the situation at the Cape,

and then a running commentary by way of 27 short chapters on wild animals,

birds, fishes and insects, plants, seasons, indigenous inhabitants and their

anatomy, garments, dwellings, possessions, character, manners, way of living,

fighting, dancing and religion. Only some twenty pages, yet crammed full of

the remarkable insights on a strange

continent and its people.

A truly uncommon work is Francois Valentyn’s Beschryving van

de Kaap der Goede Hoope, met de zaken

daartoe behorende (Vol 10) published in 1724.

Although the writer had no first-hand travel experience at the Cape, he had

access to the VOC archives, and from there comes a fine early map of the Cape,

the first printed account of Governor van der Stel’s 1685 epic journey to Namaqualand, as well as the lesser known Starrenburg’s

trek into the Sandveld in 1705. The

latter part of the book deals with Mauritius, and there is also a fine

map of that island.

The next two items were in French, by two

clerics, the Abbe de Choisy, and Pere Tachard.

Both of these clerics were en route to Siam,

where their embassies were welcomed in the hope that this would keep the Dutch

at bay in that part of South East Asia. Choisy's account: Journal du Voyage de Siam, from 1686 (this is the oldest travel

book in the collection) is in the form of a diary, and is written in an

attractive style, telling about their visit to the Cape, details of the voyage

and experiences in Siam. The book is a classic that has repeatedly been

reprinted due to the importance of this particular embassy.

Tachard, who was a respected mathematician as

well as a cleric, led the second such expedition in 1687.

The voyage is described in Second Voyage

du Pere Tachard et des Jesuites envoyez par le Roy

au Royaume de Siam. Part of the book touches on the Cape of Good

Hope, where the governor, Simon van der Stel and the visiting commissioner of

the VOIC, H A van Rheede tot Drakenstein, entertained the French party and gave

them a tour of the settlement, as well as helping them with their scientific

and astronomical observations. For

this the governor was reprimanded later, as France was technically at war with

the Dutch.

Then a classic tale of travel, survival and

adversity: Voyage et Avantures de

Francois Leguat & de ses Compagnons en deux Isles desertes des Indes

Orientales. Francois Leguat was a French Huguenot who had fled France to Holland

after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

One Marquis du Quesne had first considered Reunion as a possible colony for

Huguenots, but after the French took that over, he fitted out a small

frigate, L'Hirondelle to reconnoitre the Mascarene islands, and to take

possession of whatever island was found unoccupied, for that purpose. In 1690 Leguat and nine male volunteers

boarded L'Hirondelle for Reunion which they

believed had been abandoned by the French.

Instead he and seven companions were marooned on the uninhabited island of Rodrigues.

After a year, they built a boat and sailed to Dutch-controlled Mauritius, where they were imprisoned due to France and Holland

being at war. After lengthy

imprisonment, the survivors were shipped to Jakarta to stand trial, supposedly for

espionage on behalf of the French.

They were found innocent, and Leguat and two other survivors were returned to England, where

he penned his memoirs. The book is

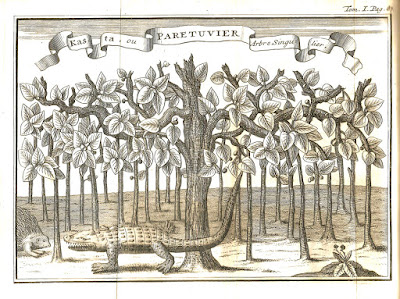

illustrated with a number of splendidly naïve engraved plates.

Peter Kolbe, another

astronomer at the Cape, spent some 8 years there from 1705-1713, which gave him

the material to compose his work The

Present State of the Cape of Good Hope.

There is a huge amount of natural

history information – most of it admittedly exaggerated and gleaned from other

sources, but his observations of the Khoi around the settlement, their

lifestyle, customs and language are fascinating.

The work is still much quoted as an early ethnographical source.

The Abbe de la Caille’s Journal Historique du Voyage fait au Cap de Bonne Esperance is next.

He was a distinguished scientist, astronomer and mathematician who in 1750 led

an expedition to the Cape. It was said of him that, during a comparatively

short life, he had made more observations and calculations than all the

astronomers of his time put together and that the quality of his work was

unrivalled. Among his results were

determinations of the lunar and of the solar parallax and the first measurement

of a South African arc of the meridian, which suggested that the earth was more

flattened at the southern pole. He

gives a lively description of the

countryside and inhabitants at the Cape during

his stay. His observations on the

voyage demonstrated the difficulties of navigation to him and led him to devise

a better method of using the moon to determine time and latitude at sea.

The Abbe de la Caille’s Journal Historique du Voyage fait au Cap de Bonne Esperance is next.

He was a distinguished scientist, astronomer and mathematician who in 1750 led

an expedition to the Cape. It was said of him that, during a comparatively

short life, he had made more observations and calculations than all the

astronomers of his time put together and that the quality of his work was

unrivalled. Among his results were

determinations of the lunar and of the solar parallax and the first measurement

of a South African arc of the meridian, which suggested that the earth was more

flattened at the southern pole. He

gives a lively description of the

countryside and inhabitants at the Cape during

his stay. His observations on the

voyage demonstrated the difficulties of navigation to him and led him to devise

a better method of using the moon to determine time and latitude at sea.

Anders Sparrman is a well-known name among early

travellers in the subcontinent, ranking with naturalists like Burchell,

Thunberg and Lichtenstein. This brilliant scientist sailed for the Cape in 1772 to take up a post

as a tutor. When James Cook arrived there later in the year at the start

of his second voyage, Sparrman was taken on as assistant naturalist,

and accompanied the intrepid explorer on his journey, reaching New

Zealand. On his return he spent several years in the Cape and

undertook various journeys into the interior.

His work, with the descriptive title: A voyage to the Cape

of Good Hope, towards the Antarctic polar circle, and round the

world: But chiefly into the country of the Hottentots and Caffres was the result, and was published in 1785. Sparrman, an excellent observer, not only

collected a wealth of specimens, but he had an eye for the country and a

descriptive turn of phrase about the people he met.

His

countryman Carl Peter Thunberg came to the Cape

as a medical doctor. After

his arrival at the Cape, he focused on learning Dutch during his three

year

stay, which was to stand him in good stead in Japan on the latter part

of his travels. In September 1772, in the company of Auge, the

superintendent of the Company garden, they journeyed to Saldanha Bay,

east as far as the Gamtoos River and returned by way of the Little

Karoo. He also met Francis Masson, who was collecting

plants for the Royal Gardens at Kew, and who shared his interests, as

well as

being accompanied by the explorer Robert Jacob Gordon during one of his three

expeditions into the interior, Thunberg collected a significant number of

specimens of both flora and fauna, and has been dubbed the ‘father of

South

African botany’ for his contributions. Four slim volumes, entitled: Travels in

Europe, Africa and Asia, made between the

Years 1770 and 1779, this third edition published in 1795-6, were the

result of his work.

South African travel writing would be a duller,

more monochrome affair if it was not for the works of the inimitable Frenchman,

Francois le Vaillant. It is fitting,

therefore, that there are no less than three examples of his work in this

collection: his so-called ‘first voyage’ in both the first French and English

editions of 1790 ( Travels from the Cape

of Good Hope into the interior Parts of Africa ), during which he had the

misfortune to lose all his equipment at Saldanha Bay when his ship was sunk by

the British, after which he recouped his fortunes and meandered along the

southern edge of the subcontinent returning to the Cape by an inland route. Also present is his second, more historic journey,

published in 1796, in which he penetrated into the inhospitable regions of

Namaqualand and Bushmanland, and even crossed the Gariep

River to penetrate into Namibia,

as has been disputed for years, but now taken as proven.

All described with the irrepressible enthusiasm of a young man out in the

wilds, full of joie de vivre, seeing dangers lurking behind every hill and

romance looming over the horizon.

One of the latter works of travels in the 18th

century was John Splinter Stavorinus’ work:

Reize van Zeeland over de Kaap de Goede Hoop en Batavia

naar Samarang, Macassar, Amboina, Suratte, this published in 1798. He was an

admiral of a small fleet which made an extended voyage covering the Dutch

colonies in South Africa and

the Far East.

He visited Stellenbosch, Hottentots Holland, Vergeleegen, Klapmuts, among other

places in the Cape, and remarks on the position of the farmers, whom he regards

as superior to the Dutch living in the towns, whom he describes as discourteous

and disagreeable, which might in part be due to the arbitrary and rapacious

government they had to labour under - similar to conditions at present, in fact. His general picture of the colony is not a

complimentary one and he paints conditions in the Cape Town hospital as being a complete health

hazard, more likely to spread disease than to cure.

A significant contribution to social history at the Cape

during the latter years of the Dutch rule.

Robert Percival was the officer entrusted by

General Craig to crush resistance at Muizenberg during the conquest of the Cape. He was

the first to enter Cape Town

and there he remained till 1797. On

his return he published a narrative of his journey and a description of the

country, under the title: An Account of

the Cape of Good Hope, containing an Historical View of its original Settlement

by the Dutch, and a Sketch of its Geography, Productions, the Manners and

Customs of its Inhabitants, which

was translated into French in 1806. This

French edition is part of the collection, and though rather thin, is not

uninteresting, and was warmly praised at the time.

His slating of the Dutch settlers and especially of their cruelty to the Khoi,

their sloth, inhospitality, and lack of social graces, are severe. However, he praises the Cape climate as best in

the world and advises the British government, who had just restored the province

by the treaty of Amiens,

to reoccupy it.

After the takeover by Britain, it is

only natural that British travellers and views should become more common. One of the earlier, and certainly more important

accounts, was John Barrow’s Travels into the Interior of South Africa,

of which the second edition, complete with

fine hand-coloured plates by that great artist Samuel Daniell, also

appeared in

1806. Barrow was the secretary of

Governor Macartney, and he was despatched on a round-tour of the country

to

inform the settlers of the administrative changes, and to gauge their

opinions. His work, though marred by bias and antagonism to

the locals, is thought to be an honest appraisal of conditions

prevailing in

the colony, and as such is a treasured part of the literature of the

period.

The era

of missionaries had started. They

came in shiploads, and from the early eighteen-hundreds, missionary accounts

proliferated, from the arid interior, then up the West Coast, and along the

southern edge of the continent. One

of the enduring contributions to this genre was Ignatius Latrobe’s Journal

of a Visit to South Africa. A gentle soul this Moravian missionary, a

talented artist, writer and musician, he embarked on a tour of mission stations

along the south coast as far as the Great Fish River, and planned on

establishing a new mission at Enon.

His book is illustrated with some fine colour plates and his sympathetic

attitude to the folk he met, the understated descriptions of his travails have

won it a lasting place on even modern bookshelves.

The last

of these early works that deserve special mention is Captain W F W Owen, who’s Narrative

of Voyages to Explore the Shores of Africa, Arabia and Madagascar was published in 1833 after a

four year expedition which was undertaken to survey the entire coast of

Africa and southern Arabia. His meticulous work laid the foundation for what

we know about the geography of some tens of thousands of kilometres of

coastline to this day, as he returned with more than three hundred charts. In addition his little flotilla became involved in

subduing pirates in the Mascarenes, and attempting to quash slavery in Mombasa. He had much interaction with the inhabitants of

the ports and islands along the coast, which makes the volumes an interesting

read.

These then are the jewels in the crown of the

collection that Peter de Villiers has entrusted to me to dispose of. There are many more recent works on exploration,

wars, history and biography. All the

above will be offered for sale by auction, on our website and by means of our catalogues which

we send out to our clients at intervals.

We trust that these cultural relics will find new owners, who will appreciate

the contents and the workmanship of these precious volumes.

The auction starts on Thursday, 27th

of August 6.30pm – and bidding ends on 3rd September at the same time, and most of the lots above, as well as other offerings can be viewed and bid on at: